Some Thoughts on Willcox and Gibbs Domestics

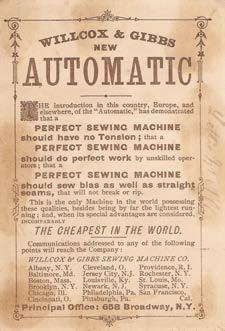

Willcox and Gibbs New Automatic Trade Card - front

Ask which was the most successful sewing machine design ever and you' ll get a variety of answers. Of course, we have to define 'successful'.

Perhaps, some would pick the Singer class 12 as the most cloned machine ever and the one that founded Singer's empire. Or maybe, folk would opt for the Singer 99 as the largest-ever selling machine.

But if we define 'successful' as the longest-produced design, we have a new contender – the Willcox & Gibbs (W&G) domestic chain-stitcher which was produced virtually unchanged for around 80 years and, with only one basic modification, for over a century.

The men behind the machine were pretty interesting characters.

Willcox and Gibbs New Automatic Trade Card - back

James Edward Allen Gibbs 1829-1902

Born August 1st 1829, James Edward Allen Gibbs was the son of Richard Gibbs, a Virginia farmer, and Isabella Poague Gibbs from Connecticut. As a child he worked on the family farm and at the cotton-carding business on the same site.

After a fire destroyed the carding mill, James then left home and attempted to set up on his own, but this and other ventures failed - although he did meet his wife-to-be, Catherine, the daughter of a sawmill owner for whom he worked.

So how did James get started in the sewing machine business? During these years, like most people, he rarely saw the outside world except what arrived in the papers of the day. In 1855 James came across a picture (a woodcut) of a Grover & Baker machine in a newspaper. The Grover & Baker machine was being sold all across America and was advertised regularly. He was transfixed by this new gadget that had the potential to change the world.

The popular myth about how he got into the sewing- machine business has it that he saw a picture of a Grover & Baker and recognizing its potential, attempted to build his own machine.

We are asked to believe that, as the picture only showed the top of the machine, he presumed that only the one visible thread was used and, in trying to discover how a stitch could be formed, invented the rotary looper which was to become the main element of all W&G chainstitch machines. Further folk law has him whittling the first experimental hook from a twisted piece of mountain ivy.

It seems this breakthrough, in 1855, wasn't seen as terribly important to Gibbs for it wasn't until 1857 that he applied for the all-important patent. The inspiration to get patent protection is said to have come from his seeing an early Singer No. 1 machine and realizing his model was superior.

An early W&G hand machine with glass tension discs and an elaborate gantry to support the hand wheel.

He sold half his interest in the idea to sawmill owner, John Ruckman, and used the money to t ravel to Washington, then the centre of mechanical innovation, to check out other machines on the market. He produced a patent model, submitted it for approval, and was granted a patent on June 2nd 1857.

His next step was to finance the project and this is where James Willcox and his son Charles enter the story. The Willcoxes would have fitted neatly into today's Dragons Den TV programme. They were entrepreneur investors, putting their capital into new-fangled inventions. Willcox Senior had made his fortune in the hardware business and was attracted to the Gibbs machine. Gibbs explained their first meeting:

"I was in Philadelphia in 1857 selling the first of my first two inventions in the office of Emery, Houghton and Company, when James Willcox came in. He remarked that he was a dealer in new inventions, and asked me to come to his shop in a Masonic Hall and build a model of my machine for him."

Now, all the new company had to do was manufacture the machine. Rather than set up a factory, hire labour, etc, the fledgling business took another route and sought out an existing engineering company to do the work. The choice of Brown & Sharpe (B&S) of Providence, Rhode Island was a felicitous one. B&S was a company supplying the clock-making industry. Although not at the forefront of the industry, the company was keen to develop the new 'American System of Interchangeable Manufacture'. So, if B&S was going to be involved, the job was going to be done properly.

It took over two years to design and build the special tools necessary to fashion the machines with the intention of every part being totally interchangeable. This practise was common in gun manufacture at the time but most sewing-machine companies were still working on the file-it-to-fit system where individual parts were hand modified to fit as machines were built up on the bench.

After much trial and tribulation, the first machine came off the production line in late 1858. With the manufacturing process so streamlined, B&S was able to produce 5,000 machines a year from day one.

It must have been some time before set-up and development costs were covered, but I'm guessing the firm was firmly in the black by 1875 when the one major design change was introduced. B&S had launched the W&G sewing machine and W&G had launched B&S as the premier machine tool manufacturer.

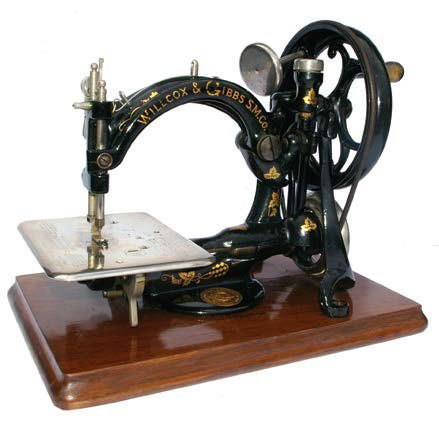

The W&G Automatic chainstitch machine we all love

Up until then, the thread tension was fairly conventional, albeit with glass tension discs rather than the commonly used steel. Let's think about that for a moment. Whilst virtually every other maker was simply pressing out a pair of dished steel washers, sometimes plated, sometimes not, to act as a tension – W&G went to the considerable expense of making them from glass. Yes, it cost more, but the moulded-glass discs had a better finish, would never rust and you could even see when they got dirty...

But it was still something that had to be set and adjusted by hand and in 1875 the "Automatic" tension model was introduced for the domestic market. The glass tension was continued on some specialist industrial models but the automatic tension served for around 75 years of domestic-machine production.

Offices were opened on Broadway, New York City, and soon sales were booming for what was, initially, a treadle-only machine. It was only when the Company looked at export markets that the idea of a hand-crank version was explored.

Shipping complete treadles would have been expensive and W&G's research showed that hand-crank machines were favoured over treadles in Europe. And, if hand-crank machines were to be sold in Europe it made sense to just ship the heads and have the necessary additional parts made locally. Naturally, W&G looked to Coalbrookdale in England for a solution. This was where the Industrial Revolution began and the world's first cast-iron bridge still stands there today.

James Gibbs' other chainstitch machine ( see ISMACS News 98 for an article on this machine )

The basic idea of a flywheel held above the drive pulley on a gantry was quickly decided upon. A number of gantry designs were produced and drawings still exist in the Coakbrookdale archives.

One, highly-ornate gantry design still exists today in the Maggie Snell collection, but the version chosen for production was less fussy. Even this was soon discarded for a smoother design, cheaper to produce and less likely to give problems in the casting process. The first wheel designs were also soon rejected for a similar version with smoother spokes.

The machine with its gantry and wheel were mounted on a wooden base, initially quite deep and of solid wood but this was later superseded by a thinner, veneered, base.

To sell the machines in Europe, a UK base was set up in London, initially in Montague Street but later in the more-prestigious Regent Street. James Gibbs, who had fought for the South in the Civil War, died in 1902 aged 73.

In the USA, geared hand-crank and later electric table-top versions were produced on cast-iron bases, which more than doubled the weight of the machines but certainly kept them from wandering around the table.

The fancy sewing box cover for the full cabinet machine, showing a close-up of the divided tray.

A good number of cloned machines appeared in the late-19th century, principally by Drus & Murphy, Eldridge, and Frister & Rossmann. W&G continued building industrials after the last domestic machines were made in the 1950s. The company produced a vast number of highly regarded lock-stitch industrial models and was a major supplier of parts and accessories to the sewing-machine trade.

Up until the 1990s W&G existed as an electrical- supplies distributor but the name disappeared at the end of the decade when it was changed to Rexel Inc.

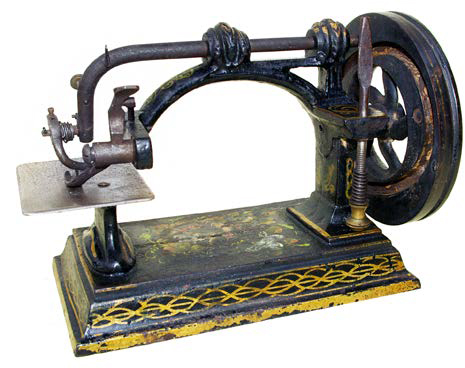

The Frister & Rossmann clone of the W&G Automatic

A few asides on the machines:

The W&G uses a very special needle with a groove all the way up the shank. This groove located on a miniature pin within the needle bar to give precise setting of the needle. Fitting other needles can damage the pin.

The needle is held in its bar by a collet system with a nut closing the end of the bar around the needle, giving a very firm grip. To avoid this precision job from being over-tightened and the thread stripping, W&G provided a miniature spanner around 2-inches long in the tool kit.

W&G manufactures are sometimes found with the base-mounted badge on the rear and quite often with a scalloped base. It was expediency. The ultra-thin cast-iron base flange was prone to damage when being removed from the base. To minimize wastage, wherever possible the damage was concealed by repositioning the medallion and by milling a scalloped edge around the rim.

A fancy case for the glass tension disc machine

The W&G was probably the quietest machine ever made. The system of connecting rods to operate the rocking arm and the tensioning mechanism meant no noisy gears. And with the only reciprocating parts (the needle bar) being driven directly from the rocking arm via a spherical bearing, there was no backlash anywhere to create noise.

The fine tolerances used to produce the W&G can works a little against us today. Just a little surface dirt on the needle bar, for example, can seize up the machine. However, I've yet to see one that can't be brought to life with a thorough cleaning.

The fancy sewing box cover for the full cabinet machine