Who Invented the Sewing Machine?

To the Victor, the Spoils

ISMACS secretary Graham Forsdyke gets hundreds of e-mails each week requesting help on researching old sewing machines.

The most frequent query from the media is: "who invented the thing anyway?"

GF attempted to address the issue in a lecture at Kent State University, Ohio, USA, a few years back.

In an attempt to ease the flow of e-mails, perhaps it's time we published the speech so that you can sift the evidence and decide for yourself.

WE ARE gathered here today to resolve one of the great unsolved mysteries of the 19th century who invited the sewing machine and also to ask ourselves: who gives a damn.

The invention issue is not so much a question of whom but more, which country and favourite son should be, accorded the honour.

There are five contenders for the big honour from the USA, Germany, France, Russia and the United Kingdom.

When man attempts to mechanise something previously done by hand or in nature, he attempts to emulate what went before. Airplanes are a fine example. Man first tried to copy the birds. He would fashion a pair of wings, perhaps in the deluxe version stick on some feathers, climb to the top of the Eiffel Tower and step off. The large dent in the sidewalk told him he had got it wrong.

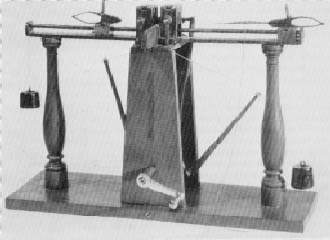

An early attempt to emulate hand sewing by machinery. This is John Greenough's patent model of 1842

And take motor cars. The first ones were called horseless carriages simply because they took a carriage, removed the four-legged power supply and added an engine.

Even cars run on horse power the higher the number, the faster the vehicle. It was the same with the sewing machine.

Consider the simplest form of sewing. A threaded needle is passed through the cloth, turned around and passed back a little further along to produce a simple stitch.

So it's reasonable to assume that the first attempts to produce a machine would try to emulate hand sewing in its basic form. But consider the difficulties of achieving by machine what is so easy by hand.

You could start with a threaded needle held, perhaps, in a pair of pincers and have the machine push it through the cloth. Then even get another pair of pincers to pull it through from the other side. But that's where the easy stops and damn difficult begins.

Now we have to turn the needle through 180 degrees and pull the stitch tight.

Charles Weisenthal

The first of those problems was tackled successfully by Charles Weisenthal, a German mechanic working in London, England, and financed by the British nobility.

In 1755 he invented a machine aimed at embroidery work with a two-pointed needle. Therefore the first two pairs of pincers could shuttle the thread back and forth through the cloth to produce a crude stitch.

No turning of the needle was necessary but our Charles didn't or couldn't tackle the tightening of the stitch problem. And it was a bigger than first appears, for as the seam progressed the amount of thread on the needle gets shorter and the amount of movement to tension the cotton reduces.

OK, let's evaluate this. A German inventor who did at least get his feet wet in the sea of experimentation. It's got to be worth something but not a lot as none of his idea eventually found their way into a successful machine.

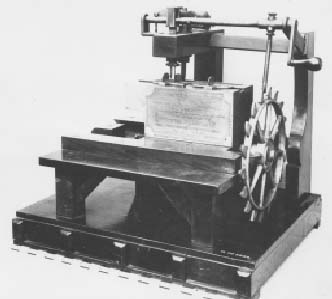

The replica of Saint's machine with which Newton Wilson taunted Howe in 1876

Thomas Saint

It wasn't until 1790 that the big breakthrough came and that was the realisation that perhaps the needle didn't have to pass all the way through the cloth to produce a stitch.

The man who almost changed the course of history was an English cabinetmaker who, when he wasn't busy producing high-class furniture for the landed gentry, pursued his part-time hobby inventing.

Let me take a small diversion here to explain the mysterious working of the British Patent Office at the time. Instead of, as today, applying for one patent at a time it was possible, back in 1790, to make one application for a whole bunch of ideas.

Thus it was that when Thomas Saint, master tradesman, arrived at the office on July 17 of that year to be issued patent No.1,764, it covered, amongst other things, paints, glues, clog making and a sewing machine.

Now the multi-invention patent might have saved time for the patent clerks and money for those looking for legal protection, but the system had one big flaw.

You had to file it somewhere. It wasn't the patent clerk's job to decide on the importance of the various inventions, so each batch got listed simply under the subject of the first patent in the bunch.

Thus Thomas Saint's revolutionary sewing machine was filed under glue, bookbinding for the use of. And that's where it lay for 100 years until discovered by William Newton Wilson, a sewing machine manufacturer, whose hobby was researching the early days of the history.

The find did little to alter the record books. By the time of the discovery others had become millionaires from patents which, if Saint's machine had been discovered earlier, would never have been approved.

Newton Wilson was one who had suffered at the hands of Singer's lawyers years earlier. It was too late for him to claim recompense on the grounds that the later patents were worthless but he got his revenge in a remarkable way. He built a replica of a Saint machine made from the drawings submitted with the patent.

He proved it worked. He then booked space at the 1876 Centennial Exhibition in Philadelphia right next to the Howe exhibit. Thus visitors to the celebration were confronted with a gigantic Howe display with the words "Elias Howe, inventor of the sewing machine 1846" emblazoned across the façade. Next to it, on a smaller stand, was just one machine that replica and the words Thomas Saint, inventor of the sewing machine, 1790.

On the plus side Saint certainly invented a sewing machine with all the attributes of those we know today. That should put him right to the top of the pole. But there's no evidence to say that he actually built a machine and Newton Wilson admitted that he had to make a number of modifications before it would properly work,

One small aside here. I've spent the past 20 years delving into the history of the sewing machine but Newton Wilson, the man who discovered the Saint model, was doing the same thing in the end years of the 20th Century.

He was in the process of writing a book on the subject when he died and must have accumulated a vast library of research material.

When he died the Saint replica was donated to the Science Museum and I reasoned that it was quite probable that his paperwork went to the same home.

Now, I'm not sure how it works in the USA but in the UK if you write to a government department and suggested that PERHAPS something might be on the file and could they please have a look IN CASE it's there, the inevitable happens.

The researcher does nothing for a couple of weeks and then writes back to say that a thorough and exhaustive search has failed to reveal the requested material.

My method of preventing this is to write saying that I KNOW the material was deposited in a certain year and requiring sight of it for research purposes. Even this doesn't always work but I've had some success.

Thus I wrote in those terms to the Curator of the Science Museum and sat back to await the result. Three weeks later I got the standard "nothing found" letter.

It was only years later when that official had become a firm friend that I discovered he had put three men on the search for two weeks working on the theory that if I'd said it was there, it must be, and it was the museum's job to find it.

I still haven't told him the truth and if I want to remain friends it's far too late now.

Barthelemy Thimonnier

Now it could be agreed that all those small-time inventors coming up with unfinished ideas were interesting, but what we need is a sewing machine that was practical and of proven worth. This is it.

The time is 1830, the scene revolution-torn France and the place St Etienne, 200 miles south of Paris.

There lived a tailor called Barthelemy Thimonnier I'm going to call him Bart as I've never said his full name the same way more than twice.

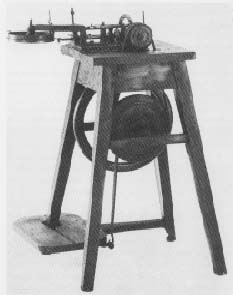

He produced a machine, a with a hooked tambour needle, which produced a very simple form of chain stitch.

Some historians claim that it was really an attempt to produce a mechanised embroidery machine, but whether that is true or not, the fact is that this wooden wonder did actually join cloth.

Although the operator had to feed the material by hand it could sew any length of seam, and curved seams at that.

Bart obviously appreciated the sewing qualities of his invention and soon had 80 machines built and in operation in a Paris factory, fulfilling contracts for uniforms for the French army.

The version of the Thimonnier machine in the London Science Museum

This should have been the start of the sewing machine taking its place in the clothing world. But this was France with revolution in the air and local tailors, fearful that such machines would cost them their jobs, formed into a mob and descended on the factory.

It took just an hour to force entry and then the mob systematically set about destroying the machines. They were reduced to little more than matchwood, piled in a corner of the factory, and set alight.

Bart could only watch as his future burned. As the flames grew higher he knew that the rabble would next turn its attention to him. He rapidly gathered his family around him and with what few possessions he could carry fled the city south to the relative safety of his hometown St Etienne.

But he wasn't defeated and four years later had developed an improved model now capable of 200 stitches per minute.

The revolution of 1848 virtually brought French industry to a full stop and Bart had little chance to promote the Mark 2 version. A Mark 3 followed a few years later and attempts were made to market this in the UK and in the USA.

But by then, with progress made by other inventors, the French machine looked ungainly and had been totally superseded on technical merit.

The story doesn't have a happy ending. Bart had sunk every penny into trying to resurrect his machine but eventually his own money and that of his sponsors ran out and the man that the French claim to be the one true inventor ended his life as part of a traveling show, displaying in a tent his wonderful sewing machine at 10 cents a time.

So where does BT stand in our Hall of Fame? Pretty high, I reckon. He invented a sewing machine- no doubt about that. He produced not one example but probably close to 100. They worked and he set up a successful business with them.

Unforeseen circumstances and revolutions conspired against him. That does not diminish his achievements.

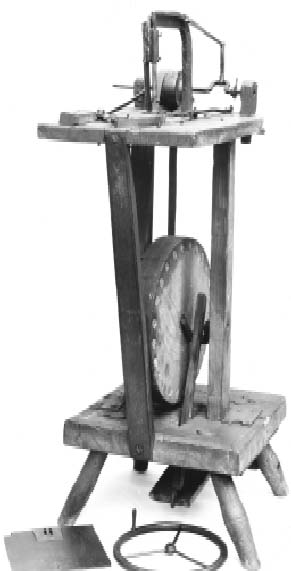

The Krems nightcap machine now in the IMCA museum

Balthasar Krems

Germany got into the act in 1810 when Balthasar Krems discovered a method of sewing turned edges of the nightcaps his company produced. It worked much like one of those old-fashioned circular knitting machines and used a tambour needle with a hook.

Some historians put the devise as early as 1800 but there is no firm evidence of this. There was no patent taken out but the machine was certainly made as one is known to have survived unto today .

The machine was very limited in its application.

Elias Howe

Elias Howe was born in 1819, the son of a Massachusetts farmer who had some income from making cards for mechanised cotton mills in New England.

He left home at 16 to train as a machinist and served time in a machine shop that produced industrial machines and in Boston with a company that produced scientific and nautical instruments.

Perhaps aided by his textile experience he produced a sewing machine which in many ways leant heavily for inspiration on the loom with its shuttle.

From the start his problem was finance. He earned $5 per week which would barely support his family. He needed $500 to get the first machine made and developed.

In Sept 1844 he sold income rights to half his patent to a wealthy friend, George Fisher, in exchange for board and lodgings for himself and his family and the cash to construct the machine.

He spent six months on its construction and then he and Fisher tried to interest others in the machine. For two years they demonstrated it in Boston but did not sell a single model.

Howe's patent model now in the Smithsonian

A lot of economic reasons have been put forward for the machine's failure to succeed from the high initial cost to not attempting to sell in a better market New York City. But probably the more likely case was its sheer inefficiency.

It did sew well, six inches at a time The fabric was hung on pins and could only sew straight seams. Fisher lost heart and considered the money lost.

Howe sent his brother Amasa to England. Amasa spent months taking the machine around manufacturers in major cities with little success.

Eventually he found a corset maker called William Thomas who bought the machine and the British rights for £250, around $1,000.

Because of the obvious limitations of the machine Thomas wanted more for his money. He insisted that the inventor himself should come to London and work at improving the machine.

This was agreed and Howe arrived in the UK where he spent some months but got nowhere.

At one stage he asked Thomas to provide the funds to bring his wife and family over to join him.

It was all to no avail. Either Howe couldn't deliver or Thomas demanded too much or the machine just wasn't capable of providing what was needed and the business arrangement broke up in an acrimonious fashion.

Howe had not saved any money and found himself destitute on the streets of London owing money and threatened with debtors' prison.

But the American tells the story differently and actually claimed that Thomas had defrauded him and taken advantage of his circumstances. According to Howe, as well as the written contract, there was also a verbal agreement that Thomas would pay Howe $5 for every machine the corset maker would sell.

Thomas denied this and counter claimed that Howe's invention itself was worthless without drastic modification.

Eventually Howe borrowed enough cash to buy steerage tickets for him and his family and finally arrived back in NYC flat broke.

And there he found that much had happened in his absence. All over the NE states small and some not-so-small companies had sprung up, all making sewing machines and all in one way or another using certain concepts enshrined in his patent.

The fact that these machines were actually working and his didn't wasn't important. He had that vital piece of paper that was to make him the second-richest man in the world and that's before the days of oil.

And he got rich by getting sufficient funding together to start a series of actions against every one he could reach.

Some capitulated, no doubt advised by their lawyers, some slipped away and quietly continued producing machines anonymously which is why you will see so many machines from the 1860s with no manufacturers' names upon them.

But others chose to fight Howe and chief amongst these was the young upstart, Singer.

There started a series of courtroom battles that put everything else in the shade. Singer recognised that Howe's patent the use of an eye-pointed needle and shuttle covered just about every machine it was possible to build.

He could only challenge it on one ground: that the system had been in use before Howe applied for his patent. His hopes lay in a New York inventor called Walter Hunt who Singer claimed had produced a sewing machine with needle and shuttle in around 1833.

Hunt was a professional inventor with a whole bunch of likely ideas on the way at any one time. He built a machine, proved it would sew and promptly lost interest, turning his mind to other ideas including the safety pin. Hunt never patented his sewing machine but sold the rights in it to another. From the 1830s to the 1850s no more was heard of the machine, but Singer's patent lawyers tracked Hunt down, had him build a replica and displayed this to the patent commissioners as evidence that Howe's machine wasn't new.

The commissioners weren't impressed. In their view Hunt's invention had been allowed to slumber for 18 years and was then only resurrected to strangle another which was likely to convey real benefit.

Round one to Howe.

Singer then sent his lawyers to England, Germany and France, seeking patents that would show the existence of a similar machine prior to 1846.

I am sure that these detectives, for that is what they were, were as thorough as they could be for success would literally save Singer millions in license fees. But they had to contend with the vagaries of the patent offices.

Had Thomas Saint's patent been available there would have been no contest, but that wasn't the only way in which the vagaries of the British Patent Office worked against Singer.

For some years I had been aware of a British patent from Fisher &Gibbon which used Howe's eye-pointed needle and a similar shuttle. Why, I often wondered, had Singer's lawyers not pounced upon this as it preceded Howe's patent by 27 days.

The answer became clear a couple of years ago. When Singer's detectives landed on the steamer from Boston to Liverpool they would have had the choice of three patent libraries in the UK:

one in London, one in Edinburgh, Scotland, and one in Manchester.

Manchester was just 50 miles away with a direct rail link; the others were over 200 miles. It's reasonable to deduce that they went to the Manchester library.

For the next link in the story we jump to 1992 when, as part of a space-making policy, Manchester Patent Office decided to put old patents on Microfiche and sell off the original paperwork.

These were finely bound by subject in vast books and we obtained all those for sewing machines from year one to 1870.A couple of years later I was writing an article about Howe and went to the bound volume to consult the Fisher patent.

It wasn't there.

Howe's patent was firmly in place, but of the all-important Fisher document there was no sign.

Nothing had been ripped out. It was as though it had not existed.

I made quick 'phone calls to the Edinburgh and London patent offices. In both their books the Fisher patent was in place. Now remember that the book I had purchased from the Manchester office would be the very volume that Singer's lawyers had consulted.

Sloppy work by a patent clerk who had failed to send off the Fisher papers to the bindery had altered the course of history.

So Howe's patent reigned supreme. But remember the Howe model had no feed, couldn't sew more than five or six inches and all seams had to be in a straight line.

Others solved these problems. Wilson of the Wheeler & Wilson Company had the patent on a decent feed mechanism; the placement of the needle moving vertically above a work plate had been purchased and was held by Singer.

These big three battled each other and the small-time players for a number of years until one Orlando B Potter of the Grover & Baker Company came up with the grand idea. He got all the interested parties together around a table and formed the infamous Sewing Machine Combination the first real cartel and one which was to control sewing-machine production in the US and abroad for the next 14 years.

Grover & Baker had no really important patents to contribute but gained membership to the Club chiefly on the grounds that it came up with the idea.

This group licensed sewing-machine production and it was virtually impossible to legally produce a machine without its permission. And that permission came dear.

For the first seven years of the patent every manufacturer was required to pay a $15 license for each machine. Howe received a whopping $5 of that for he held the aces, $3 went into a special fund to fight anyone who might seek to infringe the patents and the rest was divided equally among the four members. Yes, Howe got another share.

When Howe's patent was renewed in 1860 the license fee went down to$7. In 1877 the last of the patents expired, despite desperate attempts to get them extended. Patent extensions are normally granted when the owner can demonstrate to Congress that he has not had a reasonable return for the invention.

Just how Howe, then the second-richest man in the world, got his first patent extension is a mystery. Well, perhaps not there is evidence of a failed bribe attempt involving Howe lawyers and a number of congressmen when the company applied for a second extension. Also on the debit side of Howe the inventor are stories that he stole his machine from a reverend gentleman in the Deep South and that he deliberately suppressed evidence of earlier machines.

He countered these with a series of bogus histories purporting to be serious studies of the invention of the sewing machine but in truth simply propaganda from Howe's vast publicity machine. So where do we rate Howe in the invention stakes? Despite all the evidence of graft and corruption, the fact that he seems a thoroughly dislikable character, he's there in the record books. Ask any American historian, ask the Smithsonian Institution who invented the sewing machine and the answer will come back Howe. He made more money from his claim than any other inventor so, perhaps, to the victor the spoils.

All that remains of Kyte's machine

Schemer Kyte

We've nearly reached the end of the road but for one consideration. Another odd-ball English eccentric nicknamed Schemer Kyte who lived the life of an early con man in the Midlands of England in the middle of the last century. Our interest in him comes from an odd and very indirect source.

The story starts in a junk shop near Shakespeare's birthplace at Stratford on Avon in 1892. A Birmingham surgeon, Lawrence Tait, was grubbing around amongst the rubbish in the yard at the year of the shop when he made an astonishing discovery.

What he found was a crude and certainly early sewing machine. It's what he did with it that interests us here. Tait was obviously a doctor with a view to the main chance and soon he was sending his find off to the British Science Museum for evaluation.

He actually, in 1893, sent a whole batch of finds including engineering tools and what he called "one old sewing machine made by Chas Kyte".

The museum sent details of the find to the acknowledged expert Newton Wilson the same man who discovered the Saint patent. If anyone could identify the machine it was he.

But Wilson was on his deathbed. There is evidence from other sources that he did not leave his home for the last 18 months of his life and probably never actually saw the machine. Certainly there is no report from him in the Museum archives.

Shortly after Wilson's death Tait wrote again to the Museum now saying that he wanted to sell the machine and again declaring that it was Kyte's work and certainly dated 1840.He didn't state a price but said he'd be happy to get back what he had paid for it. As a postscript he added that he had since found the missing shuttle and would throw this in as part of the deal.

The directors were not impressed. There was no evidence of date and not even any authentication that Kyte had made it. A reply sent to Tait from the Museum went so far as to suggest it was probably a copy of an existing machine and much later than was being suggested.

The Museum considered it a "mechanical curiosity" rather than historically important, declined to buy but said they would accept it as a gift and exhibit with Tait's name prominently displayed.

Tait was less than pleased. He claimed that the Museum's prevarication had cost him the chance to sell the machine elsewhere but, never-the-less, said that the Museum could keep the machine on loan until he located a buyer. He didn't send the shuttle, preferring to keep this ace card in his hand. The Museum has a letter from Tait asking for the machine to be returned to him in 1893 for display at a large exhibition but there is no record of this ever happening. Unfortunately the Museum appears to have done little or no research on the machine.

When they first received it there would have been people alive who knew Schemer Kyte. I've spent a lot of time on this one trying to locate Kyte's or Tait's descendants but to no avail.

And where Surgeon Tait got his 1840 date is a bigger mystery. Did he have evidence or did he pick a date out of the air making it conveniently prior to Howe and the others?

I've examined the machine closely. It certainly dates from the middle years of the 19th century. But whether it's 1840 or '50 or '60, there's no way of knowing. It's certainly not a copy of anything else as the Museum authorities suggested but there is no way of knowing if this is an historically all-important prototype of 1840 or a blacksmith lash-up using existing principals and made 10 years or more later.

But it's our job to evaluate the evidence. I've spent the last 25 years researching this subject with the maxim that at least two indisputable sources are necessary for the assumption of fact. Here we don't even have one.

So we are stuck with what we have a three-way draw for honours between the USA, UK and France. I'm still researching the subject and perhaps there is more to discover.

But what about the old USSR? Back in my early days as a newspaper reporter I remember a story issued by the Russian news Agency TASS claiming that researches in Kirdistan had proof that the sewing machine had been invented in the Soviet Union.

In those old very Cold War days the Russians were claiming to have invented everything from TV to the condom. I carefully sifted the evidence and, despite the reports, there is absolutely nothing to substantiate the claim.

So we are back to the three-way draw.

Isaac Merrit Singer

Isaac Merrit Singer has been all but ignored in this lecture because he invented virtually nothing.

But this womanising, decadent playboy a bigamist with untold numbers of illegitimate children who was eventually packed off to England to avoid embarrassing the Singer company in New York society did contribute one major facet to our story. He sold the sewing machine like nothing had ever been sold before.

He popularised a system of gradual payments, allowed free trials in the home, employed the largest force of salesmen in any industry in the world, opened up Singer shops in every town and, until fairly recent years, the company produced machines unrivalled by its competitors.

So there, in albeit condensed form, you have the facts to enable you to judge as well as any other who and which country invented the sewing machine.

So pick over the facts, assess the runners and form your own conclusions.