Caring for a Pet Lion

The Kimball & Morton ‘Lion’ sewing machine of 1868 may not be the rarest of sewing machines but it is certainly the most bizarre British sewing machine. In America, several figural machines were patented in the early days but none was successful or as lifelike as this one. The ‘Lion’ was the only British entrant in that class.

Figure 1:

The photograph in the ‘Design Register’ of a production machine taken in 1868. The bobbin winder can be seen below the table top

Alonzo Kimball was an American who came to England in the 1850s to set up a sales organisation for I. M. Singer & Co. He settled in Glasgow as its managing agent and amongst his recruits was John Morton who became the Singer agent in Liverpool.

Kimball and his staff were successful in building up the sales of Singer machines to the point when, in 1867, the Singer Company decided to set up an assembly plant in the UK, its first overseas plant.

The Love Loan factory in Glasgow assembled class 12 machines from parts made in New York. (This was before the construction of the Elisabethport factory.) Sadly for Mr Kimball, he was not made the superintendent of the new factory but another Singer man, George Woodruff, the manager of the London Office was put in charge.

Kimball and Morton left the Singer Company and started their own manufactory in Glasgow in late 1867. Their first entry in a Glasgow Trade Directory was in 1869, giving their address as 21 Bishop Street, Anderston, Glasgow.

It was to be a moderately successful company concentrating on heavyweight machines for sewing sails, tarpaulins, etc. for the Clydeside shipbuilding industry. Their domestic machines centred on Singer ‘New Family’ or class 12 clones which both Kimball and Morton would have known well.

In 1868, as a lmost their f irst foray into domestic machines, they introduced the ‘Lion’ machine. The machine was only available on a very ornate treadle base and its sewing mechanism owed a lot to the Singer class 12. Thus the machine was not patented but the shape, or form, was protected as a ‘Registered Design’ (Fig 1). Both the treadle and the machine head carry a registration mark for 23rd December 1868.

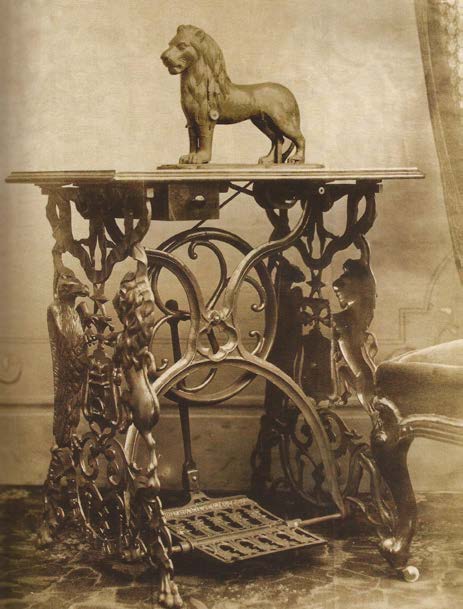

Figure 2:

One of the treadle sideplates showing the intricacy of the casting

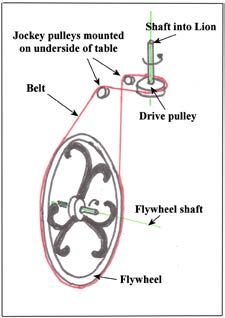

Figure 3:

The drive belt layout for the treadle

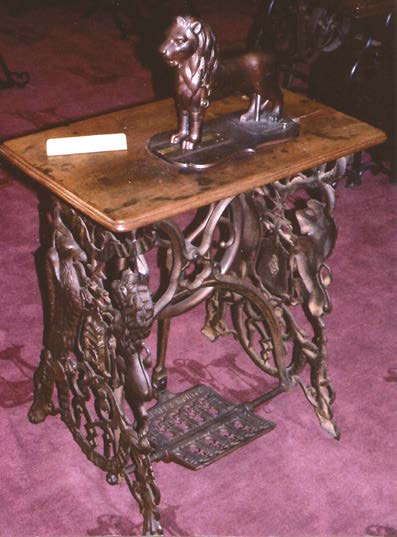

Figure 4:

The front of the ‘Lion’ machine

Its launch price was six guineas (£6.30), the same as a Singer ‘New Family’ on a treadle base, so it was not aimed at the premium market. I have not been able to find how many were made or for how long it was produced. Where I have been given the serial numbers, they are between 600 and 900. It cannot have been made for many years as Alonzo Kimball retired in 1874 and, in 1879, there was a major fire at the factory and John Morton was declared bankrupt. How many survive? A reasonable guess would be ten plus and counting.

The treadle sideplates contain both a lion and an eagle, and a picture of what looks rather like a Singer No. 2, with the legend “STRENGTH AND SPEED” (Fig 2). It is one of the most ornate treadle sideplates I have seen. I do not know which foundry supplied the castings but they are of high quality.

The flywheel is in the vertical plane and faces the operator. The drive belt follows a tortuous path because the pulley on the machine head is in the horizontal plane so two extra jockey pulleys are required to turn the belt drive through a right angle (Fig 3). The bobbin winder is mounted on the underside of the table. To wind a bobbin, the winder is rotated so that the friction wheel takes its drive from the rim of the pulley on the vertical shaft of the machine head.

It is the machine head which is the unique feature (Fig 4). It takes the form of a castiron lion standing on what looks like the base mechanism of a Singer class 12 machine. Indeed, Kimball & Morton did advertise the machine as the ‘Singer Lion’. The lion was bronzed or gilded, as was the treadle, and the base of the machine was japanned and sometimes decorated.

Figure 7:

The gear box in the Lion’s backside as viewed through the access hole

Figure 8:

The inside of the head showing the needle bar and presser foot assemblies

Figure 5:

The underside of the machine showing the drive pulley. Compare this with the underside of the Singer class 12 to see the similarities

Figure 6:

The underside of the Singer class 12

Looking at the bottom of the machine emphasizes the similarity with the Singer class 12 (Figs 5 & 6).

The arm of the Singer class 12 contains a horizontal shaft driven by the flywheel and treadle pulley. This shaft drives the needle via the Singer ‘heart-shaped’ cam and mounts a pair of bevel gears which drive a vertical shaft for the shuttle drive and cloth feed.

On the ‘Lion’ the vertical shaft for the shuttle and feed mechanisms also has the drive pulley. It is extended up into the Lion’s backside to a pair of bevel gears which drive a horizontal shaft which operates the needle just as in the Singer class 12 (Fig 7).

The Lion’s head contains the presser foot and needlebar assemblies which are very similar in principle to the ‘New Family’ machine (Fig 8).

Figure 9:

The ‘Lion’ machine in the IMCA Museum showing the front legs in position

Supported only by his back legs and tail, the lion would become tired when not used for sewing. Hence, two front legs and feet were supplied to clip onto the needlebar and presser foot bar when the machine was at rest (Fig 9).

Both head and body carry the registration diamond mark. Figure 10 shows the impression on the inside of the head on two machines. I have not seen two diamond marks in identical positions on the machines, so I presume the mark was stamped on the sand core every time the pattern was sent to be cast. This would be acceptable if one only made a handful at a time or made them to order. The tables show no evidence of a cover to shroud the Lion.

I think the 1868 Kimball & Morton ‘Lion’ is a friendly lion who likes being stroked. He is not particularly lifelike - his neck is distorted to fit the mechanism inside. We do not know who was responsible for the design but I think it owes a lot to the lions in Trafalgar Square, London, sculpted by Sir Edwin Landseer and installed in 1867 (Fig 11). Landseer’s lions would then have been shiny and new, very much a suitable prototype for Kimball and Morton’s patternmaker to work from. My Lion is all that remains of one of these machines; no treadle, no base, no shuttle drive nor feed, no front legs; chipped and worn, a tired old casting in need of tender loving care!

Kimball & Morton produced a second ‘Lion’ design in 1902. The ‘Registered Design’ diamond system was no longer in use so they patented it. It was modelled on a much more lifelike lion by the sculptor J. V. Gyorgy sitting on a clone of a Singer VS base. It was not a success. It was not as friendly or tactile!

By Martin Gregory

Figure 10:

Two examples of the registration ‘diamond’ mark on the inside of the head casting

Figure 11:

One of the Landseer lions in Trafalgar Square, London

The Kimball and Morton ‘Lion’ of 1868 (MG)

(The cover photo for ISMACS News 115)