The Lancashire Sewing Machine Company

ISMACS News

Issue 99

June 2010

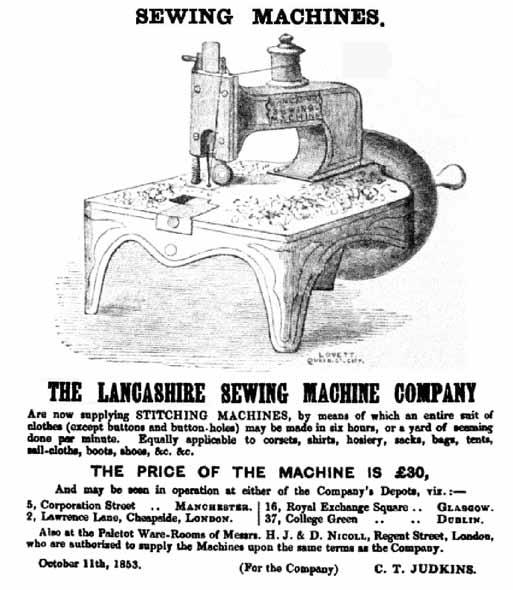

Figure 2: The Circular Needle Lancashire Machine. The machine table was about a foot square in size.

In ISMACS News #88, I mentioned I would like to obtain a copy of an article on the Lancashire Sewing Machine Company published in the London Illustrated Gazette in 1854.

Unfortunately, no one was able to provide a copy and I put the name to the back of my mind to be researched when I had more time. Then, by pure chance, I came across some information on the Company which sheds a little light on its activities.

The Lancashire Sewing Machine Company was formed shortly after the Great Exhibition of 1851 to market a production version of the sewing machine imported by our old friend, Charles Tiot Judkins. The production machine (Fig. 1) was subsequently exhibited on behalf of the Lancashire Sewing Machine Company by Mr Spackman, of Belfast, at the Irish Industrial Exhibition which opened in May 1853. Mr Spackman is credited with being the first to introduce the machine into Ireland.

According to a report of the time the introduction of the machine at his premises was apparently not without initial resistance from his work force; it was said he was "assaulted and placarded and his life placed in danger". However, he persevered and, from employing seventeen hands, he was able to employ 150 after purchasing just five of the Lancashire machines.

The design and operation of the machine at the Irish Industrial Exhibition was described thus:

"The cloth is placed in a moveable clamp under the needle, and is moved forward as the seam progresses... The needle is fixed in a portion of the machine which moves up and down to make the stitches, and it is provided with a groove on each side which the thread occupies, the eye being removed but a small distance from the point... The portion of the thread passed through the cloth is only sufficient to make the stitch. There is a small shuttle working horizontally below the cloth, in connexion with the upright needle and thread; and after the needle passes through the cloth it rises sufficiently to allow the shuttle to pass through the loop thus formed, and made above the eye, after which the needle is withdrawn, catching the thread from the shuttle and drawing it into the cloth."

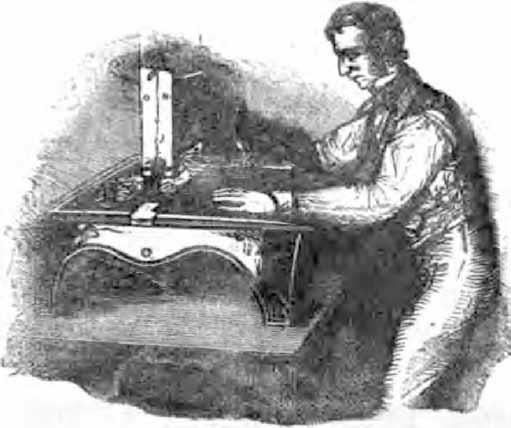

Figure 1: The Shuttle Lancashire Machine as shown at the 1853 Irish Exhibition. Note the size of the table on which it stands, which was about two feet square. The woodcut shows a Grover & Baker pattern machine! (See Fig. 3)

The machine required a little over two feet square to stand on, and could produce between 500 and 1000 stitches per minute depending on whether it was driven by hand or power.

The Irish exhibit was based on some of the 13 patents that been incorporated by the Lancashire Sewing Machine Co. starting in 1852. One of those patents was in the name of Judkins and was dated 16th October 1852. It was stated as being "a new invention as to the combination and arrangement of various parts of machinery for sewing or stitching with the use of a needle and shuttle". It was also claimed that it had never been known to have been used by another person in the realm!

[Judkins' patent agent was E. J. Hughes who had patented both the Grover & Baker and Singer pattern machines earlier in 1852, before the Patent Law Amendment Act of 1852. No. 413 of the 16th October 1852 was Judkins re-stating the earlier patent after the new Act had come into effect. Ed.]

Judkins later mortgaged this patent and after he was made bankrupt, the National & Provincial Bank sold it to Daniel Foxwell, in 1859, for £50. Foxwell subsequently issued proceedings against no less than seventy-seven British sewing machine manufacturers for 134 infringements of the patent.

Despite holding the 1852 patent, the shuttle machine sold by the Lancashire Sewing Machine Co. was (not surprisingly) said to be an infringement of Elias Howe's 1846 patent "in so much as the machine consisted in the application of a shuttle in combination with a needle for the purpose of sewing and stitching". Judkins was advised that to avoid litigation the machine should not be sold until Howe's Patent expired.

[One has to remember that in English patent law at this time there was no search, no Patent Examiners and no requirement for novelty. You patented what you liked and slogged it out in the Courts. In the view of the Mechanics Magazine, "the lawyers eat the oysters and the inventors get the shells". Ed.]

Undeterred, Judkins sought a totally different system which did away with the shuttle entirely. He mentions that he was aided in his endeavours by eight or nine "American Gentlemen" and in order to avoid opposition on patent grounds he brought the machine over to England. This machine was undeniably a Grover & Baker machine, which uses two needles to form a two-thread chain stitch. The new machine was hurriedly put into production and became available during 1853 (the same year as the Irish Exhibition), so Judkins must have moved extremely swiftly to replace his earlier shuttle machine.

It's interesting to read Judkins' own description of this "new" Lancashire machine:

"It is composed of a flat iron surface, about twelve inches square, resting upon four legs of substantial make and form. From one side of this surface an arm rises erect to the height of about 10 inches, and then passes over to the opposite side. From the extremity of the arm descends a moveable bar, to the bottom of which is fixed a needle, the eye being about half an inch from the point, and on top of the arm is fixed a reel or bobbin filled with silk or other thread. Fixed to the main shaft is a wheel turned by a handle, which can also be worked by treadle, or steam engine, that gives motion to a lever within the arm, and which moves the vertical needle up and down. Beneath the visible surface or base, is a second reel of thread supplying another needle, which instead of being straight is circular and works horizontally and consequently at right angles to its stitching companion, which descends from the arm."

"Supposing the thread to be passed through the eye of each needle, and the apparatus set to work, the process is thus performed: The vertical needle descends and passes through the two pieces of cloth to be united, carrying with it the thread to perhaps half an inch below the underside of the cloth."

"As the needle rises the thread is left behind in the form of a noose, or loop, through which the horizontal needle passes; the horizontal needle instantly reversing its motion, leaves a loop into which the vertical needle descends. Both needles thus progress making a series of stitches, each stitch being quite fast, even should its neighbour be severed. More than five hundred stitches can be made in this manner in one minute. The closeness and tightness of the threads are regulated by a screw, and as each stitch is of equal tension a great advantage is secured in the regular appearance of the work. The length of the stitch, by turning a small nut, can be increased or diminished to any degree of fineness, and perfect uniformity secured. The cloth to be worked upon is adjusted by an attendant, who with one hand turns the wheel, and with the other guides the cloth forward after each stitch."

Judkins goes on to praise the infinite variety of work the machine can carry out and suggests numerous uses. He freely admitted that he did not claim credit for the originality of the machine itself but rather that he had improved on the ideas of others.

The descriptions used at the time may, to our ears, sound somewhat stilted but we should remember not only was the written English language far more formal, but that this was the dawn of the sewing machine industry in Great Britain; very few people understood machines for stitching and fewer still had actually seen such a machine.

Messrs. H. J. & D. Nicholl, Regent Street, London were credited as "chief introducers" of the sewing machine for practical use into England. They were apparently directed to exhibit one of the Lancashire Company's machines and examples of its work to the Royal Family of Belgium who were at the time staying at Windsor Castle. "One or two machines were used to produce more stitched work in less than four hours than a tailor could in three weeks".

Scotland was also covered, with Mr Darling of Glasgow giving an interview to the Glasgow Chronicle on the introduction of the Lancashire machine from America, where it was said the invention had passed its probation and was in extensive operation including in Sing Sing prison, New York, where it was successfully and economically used by convicts.

In his article (ISMACS News #87), Martin mentioned that Judkins had castigated the Times newspaper over a claim that Mr Darling had introduced the sewing machine into this country. From Mr Darling's interview with the Glasgow Chronicle, it is clear the machine in question is the one being sold by the Lancashire Sewing Machine Co. So why Judkins was so upset is not clear; perhaps the article did not present the machine in quite the right light, or maybe Judkins felt he was being upstaged by Mr Darling.

Fig. 3: Grover & Baker industrial model.

The advertisement (Fig. 2), which dates to October 1853, gives the addresses of four company depots in Manchester, London, Glasgow and Dublin but does not give any details of where the machines were made. The woodcut of the Lancashire machine used in this advert is exactly the same as the one in Martin's article. Note it appears to show a three-legged machine despite Judkins' description.

Bradbury always claimed to have produced the first Lancashire machines in 1852. If this is the case then those first machines would have been made by the Sugdens and Bradbury partnership and may have been shuttle machines with three legs, even though described by Judkins himself as "four-legged".

Later Bradbury advertisements show a circular needle machine with three legs. The surviving example in Glasgow is of that design so it is possible Bradbury's never produced the shuttle machine, nor the four-legged Lancashire machine.

Perhaps after Judkins found he couldn't retail the Lancashire shuttle machines he, the Sugdens and Bradbury went their seperate ways. Intriguingly, there is a later documented reference to Bradbury's ceasing to produce a shuttle machine due to "patent problems". I don't know whether the Lancashire Sewing Machine Co. was simply a trading name used by Judkins or whether it was some form of formal partnership; nor when the name stopped being used. The last mention I have come across for the company's existence is in 1855. In June of that year, Judkins was petitioned for bankruptcy which could well have spelled the demise of the Lancashire Sewing Machine Co.

David G. Best

bradbury1852@lineone.net

www.bradbury1852.co.uk

www.sewmuse.co.uk