Getting to Grips with Judkins

Graham Forsdyke answers just a few questions about Charles Tiot Judkins

by Graham Forsdyke

ISMACS News

Issue 54

January 1997

A lot of the story of Charles Tiot Judkins is a complete mystery. Just what an American was doing in Britain in the 1850s, and beyond, promoting sewing machines is a matter of guesswork.

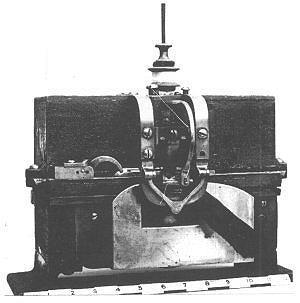

He first surfaced in quite a big way at the Great Exhibition in 1851 with a machine made by the Lancashire engineering company Platt Brothers.

This machine, with crude cloth retaining device, created little interest and he didn't even bother to patent it.

Rather that persevere with his own design, Judkins instead got hold of one of the then state of the art Grover & Baker machines -- at this stage a heavyweight monster on four cast iron legs, looking very much like a Model One Singer.

This machine he took to Platts with instructions to clone a batch, but the engineering company was in the middle of a heavy industrial dispute and was not able to take on the job.

Here history gets a little clouded. It's known that two of Platt's workforce, John Carver and George Bradbury, set up in business for themselves and produced examples of the Grover & Baker under the Lancashire and British names.

Now in the Science Museum inLondon, this copy of the first Judkins machine of 1851 was presented to the museum by Platt Brothers.

Recent research suggests that Newton Wilson was also one of the pioneers who made the machines for Judkins, but I have no firm evidence of this at the moment. In fact only two models exist, both in the Clydebank Singer collection, probably having been used in patent litigation.

In 1965 Judkins decided to go legitimate. He filed a patent in Britain which was essentially that of Charles Raymond which had been granted in America four years earlier.

And this really creates the biggest mystery of all. Raymond, having got his reciprocating hook patent in 1861, began manufacturing a New England chain stitch machine. But this still infringed patents held by the cartels, The Sewing Machine Combination, particularly for the eye pointed needle.

Obviously he couldn't afford the Combination patent fee for such a cheap machine so he packed up and reestablished business in Canada, out of reach of US patent law and in Commonwealth country favoured by the British Customs and Excise which did not levy import duties from its then vast empire.

But if he were to specialize in exporting machines to Britain via MP James Weir, what was he doing selling his patent to Judkins?

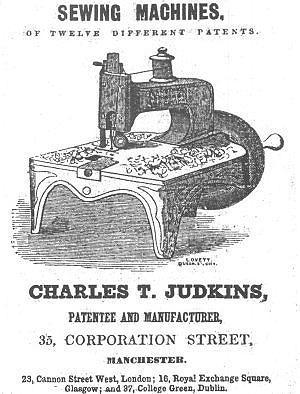

The first record I can find of Judkins selling his New England type machine in Britain is an advertisement in Queen magazine in June 1866, although a close examination of the woodcut suggests that this was what I suppose to be the second version of the Judkins import; more on that shortly.

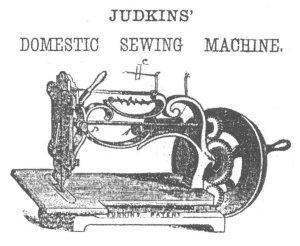

Judkins claimed to be the patentee and manufacturer of what he called the smallest sewing machine in the world.

In fact it was simply a standard New England which had been crudely customized to make it look different to the Weir machine which undersold it by a considerable margin. Weir priced his Raymond product at £2 15s (£2.75) when Judkins was advertising his modified model at £3 3s (£3.25).

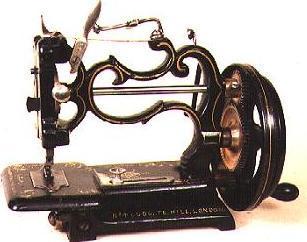

I had wondered whether Judkins had produced the machine himself as he claimed, but a close examination of the Mark One shows this is unlikely.

The way I see it, he took a standard New England, removed the bobbin holder from the top of the needle bar, cut it in half and screwed the spindle and mounting to the side of the machine. Then he chamfered off the top of the needle bar, inserted a wire guide and -- presto -- a new machine.

What I take to be the second model has the same crudely chopped off bobbin holder but has a better finished needle bar with a built in thread guide hole.

Clearly an early Grover & Baker,this is the American machine which Judkins had copied to sell under his own name in England.

I mentioned the 1866 advertisement which gave the address of No. 4 Ludgate Hill, London, which is carried on the Mark 2 machine. What I believe to be the earlier machine carries a Liverpool Street, London, address.

Although I am the first to admit that most numbers on machines mean little, for the record, the number 21 appears on the "early" machine and 732 on the "later."

Further evidence to place the machines in chronological order is provided by an instruction book where the instructions to take the thread "through the wire loop at the top of the needle bar" has been struck out and "through the hole in the top of the needle bar" substituted in ink.

The Iron monger magazine for June 1869 carries an editorial puff for the machine with a woodcut of the New England, but the text describes it as a lock stitch machine. I don't think there's much mileage in pursuing their opinion.

Around the same period Judkins was advertising in the Exchange & Mart a "new lock stitch" machine which may have been the one referred to in the editorial, and an impressive list of London branches, including a warehouse at 16 Ludgate Hill.

Then we come to the mystery of the Empress machine. It's basically the same mechanism, albeit with underfeed, but an up market version of what went before with a larger stitch plate and a little more room under the arm.

The mystery is who made it and who marketed it. We've seen how Judkins was more than happy -- as were many at the time -- to put his name on another's work and claim to be the manufacturer.

But here we have a machine which carried a brass plaque stating simply that it is licensed by the patentee Judkins Patent and the 1865 date.

Now why, if Judkins had anything to do with the marketing, didn't his name appear? If he actually licensed another manufacturer, surely the maker would want some credit. And how, if Judkins was actually licensing makers, could Weir get away with so much for so long?

My guess is that Judkins had allot to do with the machine -- same looper, same crude tension and the nastiest attempt at a four motion underfeed ever bodged around an oversized hole and a badly fitting screw.

DIRECTIONS FOR USE

FIRST

Place the Spool of Cotton Silk, or other material on the horizontal spindle; then slip a bit of India Rubber or Cork on the end of the spindle to prevent the spool from sliding off. The spool is to run perfectly free and loose on the spindle.

SECOND

To set the needle. Place the long groove in front so that the eye of the needle will conduct the thread through it exactly lengthwise of the machine; that is to say, from the front or face plate of the machine to the driving wheel. As to the height of the needle in the needle bar, it must be ...

But as to the answers to the Weir part of the problem -- I'd be glad of ideas.

This particular model (displayed at Thaxted) was quite rare until a couple of years back, but since then another two have surfaced. It came into the Maggie Snell Collection from the Newark's antiques fair and presented a series of cosmetic and mechanical challenges.

It was dirt cheap -- and so it should be. What little of the paint and decoration that survived was floating on the rusty framework and, more importantly, the driving wheel and both driven gears for the top and bottom shafts were missing.

Obviously I'd hoped that a set of gears from a scrap Weir would do the job. The holes in the Weir gears were wrong but that could be easily rectified. What couldn't be fixed was the fact that they were just too small. With the center gear fitted it missed the other two by an eight of an inch.

A check through the spares box revealed that a Wanzer center gear wheel was jus the right size when used with the small gears from a Weir, but the pitch of the teeth was completely wrong and they would not mesh. In the end I had to use the Wanzer center gear and make the two smaller gears using the Weir ones for size and the Wanzer for pitch. Thus, what could have been a half hour job, stretched into a very long full day.

The problem over the paint work left no alternative but to coat in WD-40 in the hope of inhibiting further rusting and then to cover with a layer of Shellac dissolved in mentholated spirit -- in effect the French Polish type lacquer originally used by 19th century manufacturers to protect machines.

The result is far from perfect but at least now it's a runner, handleable, and it can take its place in the collection.